Paris fashion's good time girl

Before the 20th century’s muse or supermodel, Paris fashion had its own special heroine. She was la grisette, a young woman who spent her life in the service of style. Grisettes made the dresses, lingerie and hats of Paris; they also created the laces, flowers and trim which distinguished them. Despite low wages and sweatshop hours, la grisette always found the time to dance and flirt. In the 1830s, she became a public sensation, the media symbol of la femme Parisienne.

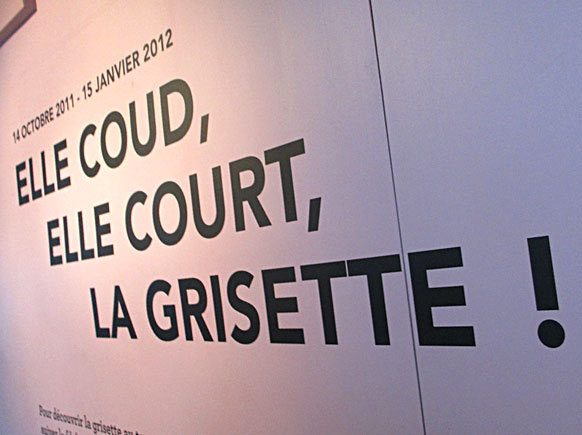

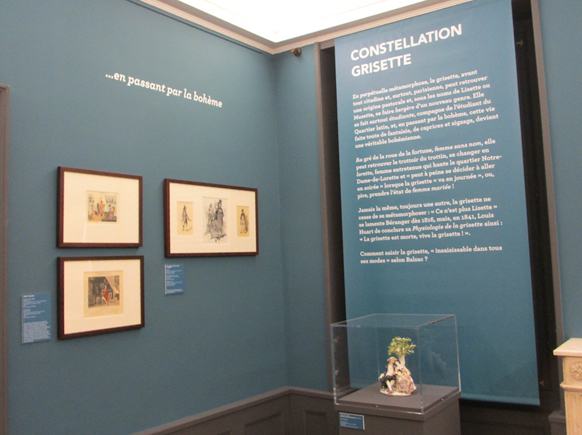

For half a century, the image of la grisette dominated both high and low culture in Paris. It is an era the Maison de Balzac has now brought back, with the first-ever exhibition about these young couture workers. It is entitled Elle coud, elle court, la Grisette! (“She sews, she runs, the Grisette!”), a reference to how the women’s profession shaped their lifestyle. The grisette of Paris legend was always in motion, darting about the city to deliver the fruits of her labour, then pouring her youthful liveliness into late-night revels.

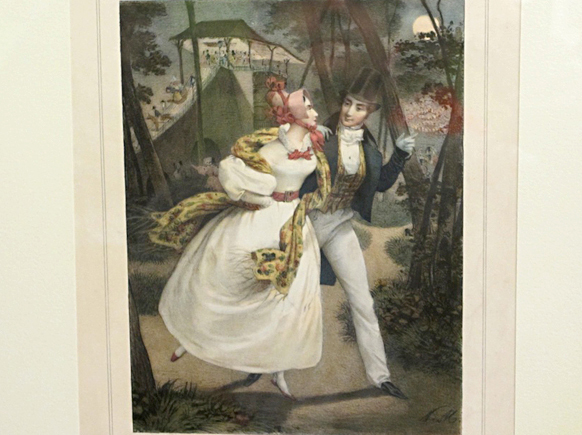

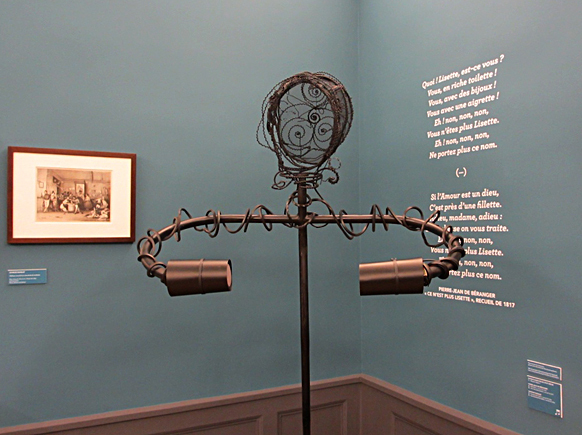

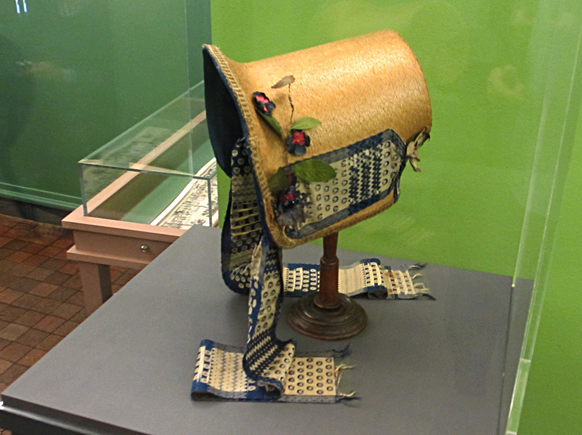

Such Parisian stereotypes were charmers with diminutive names: Mimi, Musette, Lisette, Fantine, Rigolette, Pierrette. Their party finery included satin dancing shoes, a cashmere shawl and a hand-trimmed bonnet. The grisette’s great passions were fashion and the Latin Quarter’s handsome students. But what really defined her was the fact that she was poor.

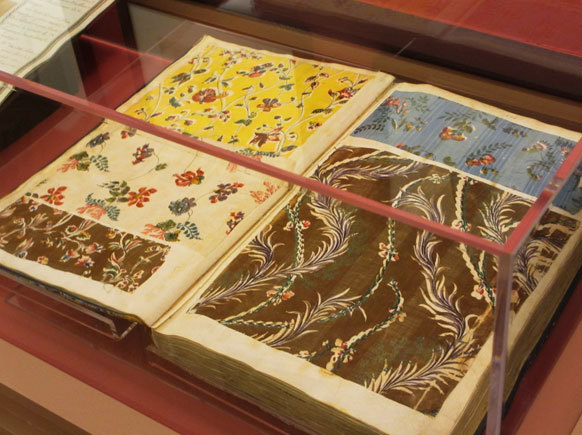

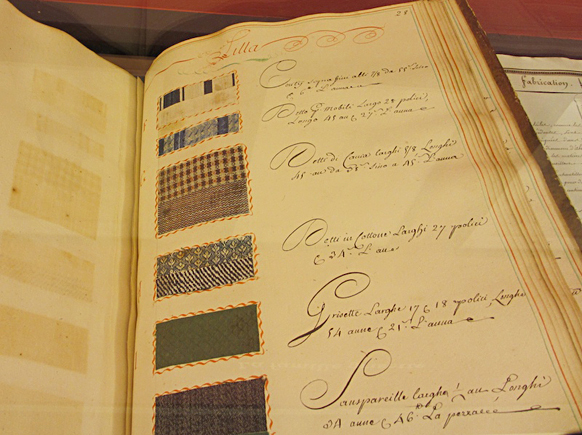

This character began taking shape in the 18th century; in 1768, novelist Lawrence Sterne wrote about a coy grisette selling gloves. The role had real-life echoes, however, in women such as Madame du Barry – who rose from work in a hat shop to become the mistress of the King. Eventually, the role’s apogee would arrive with Coco Chanel. But the grisette’s nickname came from the word gris or “gray”, the colour favoured by such workers for their dress. It stuck, even when their taste switched to colours and patterns.

The loose lifestyle of la grisette was a focus of the 1840s magazine series, “Scenes from a Bohemian Life”. These vignettes were stories by the writer Henri Murger, who based them on his own life as a struggling artist in Paris. That poverty Murger shared with his creative comrades was real. However, it was not the only thing that influenced him. Although he aspired to poetry, Murger had worked at fashion magazines, such as La Moniteur de la Mode and Le Castor. Both helped him shape the young women of his tales and her image caught the public fancy.

When Murger’s stories were transformed into a piece of theatre, its characters and their universe became the talk of Paris. Puccini took the plot of his opera La Bohème from it – and its grisette became a new kind of femme fatale.

Her character was soon a staple of Parisian life. She was painted by artists from Constantine Guys to Whistler, hailed in songs and poems, used in social commentary by writers like Balzac and Baudelaire. Idolised for her modish charm and impetuous love life, even her poverty was seen as “romantic”.

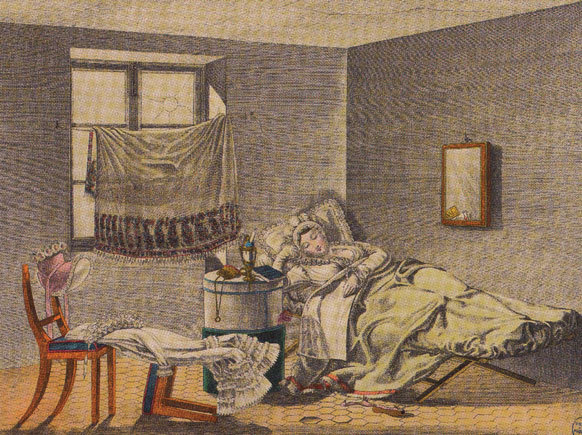

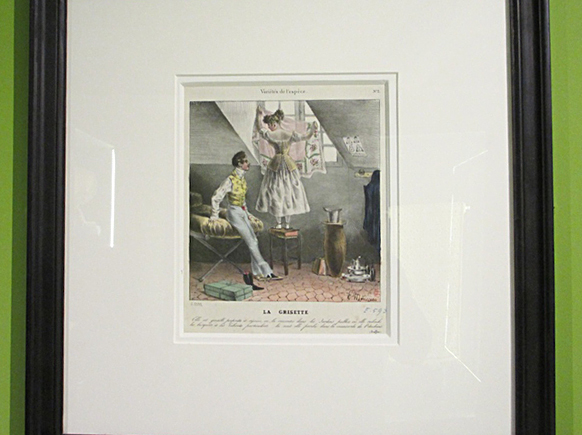

All the trademarks of la grisette became iconic. Her signature shawl, for example, was shown as serving multiple purposes. She would huddle under it in the streets, against the elements. But she also used it as a curtain to create privacy. (In the small rooms where she lived, this was a necessity). The shawl also offered a key to her moral character, since it was assumed grisettes could be “bought” with luxury garments.

Because fashion occupied almost all her time, la grisette was always shown as both pretty and stylish. However tight her budget, she was “coquettish” and “unique”. Grisettes helped an archetype that endures today: the Parisienne with a natural talent for elegance.

Huge amounts of ink were spilt to analyse her. In addition to the grisette’s role in songs and theatre, she features in works by Balzac, Victor Hugo, George Sand, Eugène Sue, Auguste Ricard and Paul de Kock. She is found in social portraits such as Les Français peint par eux-mêmes (“The French Painted by Themselves”) and in the pseudo-scientific collections known as “physiologies”. She is at the centre of treatises such as Louis-Octave Uzanne’s La Femme à Paris or Ernest Desprez’s Les Grisettes à Paris.

The public owed many of its perceptions about her to visual artists, for caricaturists and fashion illustrators fell in love with the subject. Foremost among these portraitists were Henry Monnier and ‘Gavarni’ (Guillame-Sulpice Chevalier). Their depictions offer a kind of erotic fantasy, a life in which work and frivolity alternate. In them, la grisette huddles around a meagre meal, rushes off to a dance, weaves in and out of the city crowds. Equally, however, the artists picture her private moments – sleeping off a heavy night or plunging into a love affair. Whatever the scenario, however, its setting is simple. For urban myth housed all grisettes in garretts high under the rooftops.

This character symbolised the new Paris of Haussmann and her adventures expressed the freedom of his boulevards. She loved to dance at student balls and eat crêpes in a café (or roasted chestnuts in the street); to window-shop at length and patronise the theatre. Like Baudelaire’s flaneur, too, she haunted the covered passages.

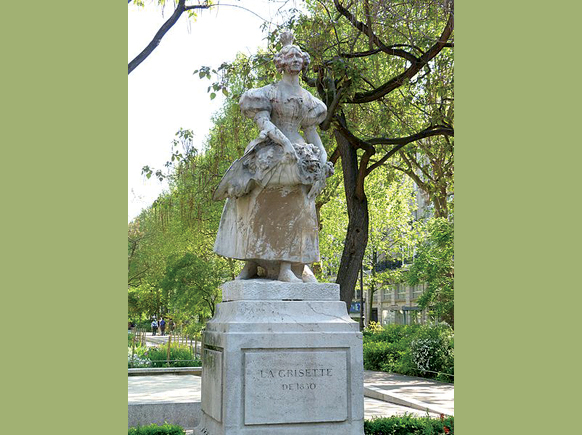

Her image is as elusive as it is evocative. A grisette’s reality was one of arduous work, from morning until midnight, for pitiful wages. Yet it was these young women, in their faceless thousands, who enabled Paris to conquer the world of fashion. The myth of la grisette remains their sole monument.