Paris retakes the photo

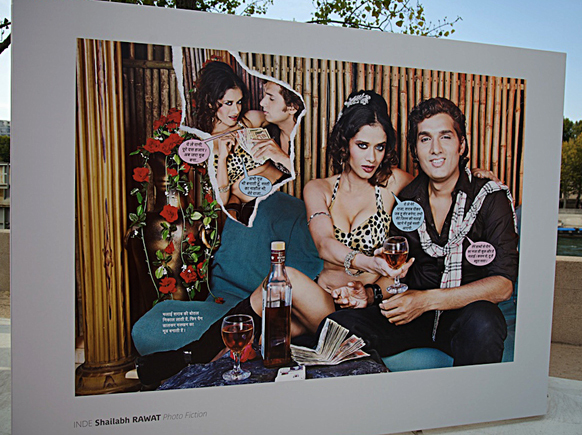

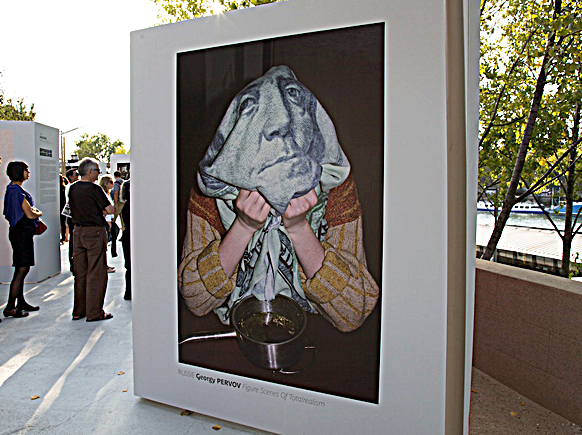

Every autumn, Paris holds a string of events intended to honor the art of the photograph. The largest are grand and official, such as Paris Photo at the Grand Palais, the Salon de la Photo at the Porte de Versailles and the Photoquai 2011 by the Musée de Quai Branly. The latter, free to all and open 24/7, is hosting work by 46 talents from 29 countries.

Alongside such sprawling shows are others in museums, galleries and foundations. Each has its own special presentation of the photo.

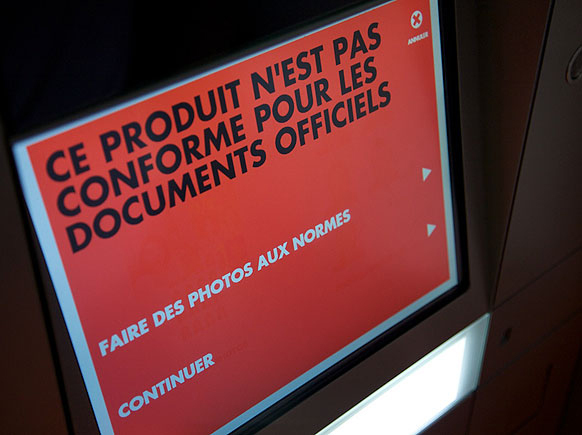

This year, all follow a summer of DIY lensmanship that started in the humblest institution – the photo booth. It began with the modernisation of Photomaton. This ubiquitous national chain enlisted Philippe Starck for their re-design, which includes touch-screens and glowing vermilion stools. So far installed in just a few sites (such as Châtelet métro station, PhotoQuai and the Pompidou Centre), the new booths have become a popular hangout.

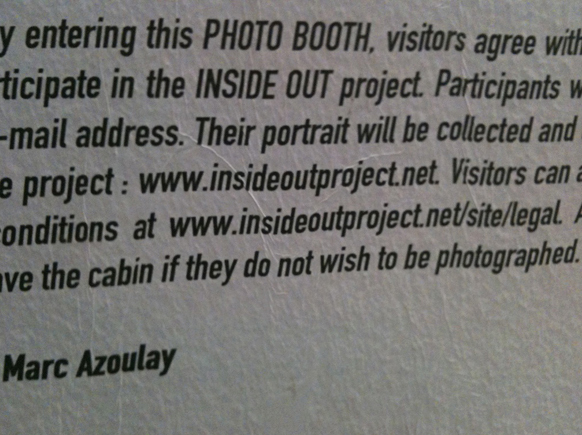

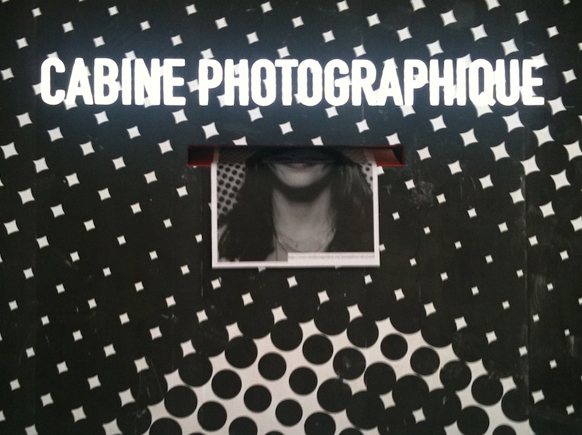

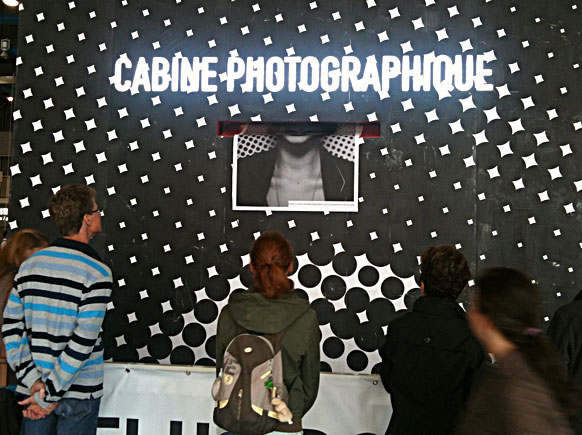

At the Beaubourg, new Photomatons sat next to the Inside-Out Project, an online initiative with a two-story tall “photo cabinet”. Part of a global effort by the French artist JR, crowds were mesmerised as its poster-size images fluttered out of a slot on the mezzanine to drift downstairs. JR envisions users papering the world with their portraits but many patrons seem too attached to part with them.

Using the photo booth as art has a history – and retro booths at spots such as the Palais de Tokyo have been around for years. But even Chanel used a booth in its latest print campaign. With their harsh lights and constricted space, however, photo booth portraits are usually personal more than iconic.

But Paris’ mythical Studio Harcourt wants to change that. They have developed a special photo cabine that promises glamour. Since their name is behind it, this has caused a stir. After all, Harcourt has been in business since 1934. Funded by the press barons Jean and Jacques Lacroix, its success came from two other co-founders. They were Robert Ricci (the power behind his mother Nina’s maison de couture) and Germaine Hirschfeld, a photographer who worked as Cosette Harcourt.

Hirschfeld was a Jewish woman who, before World War II, espoused one of the Lacroix brothers. Together, they created a magazine called Vedettes (“Stars”), as a vehicle for their studio’s photographs.

Harcourt had trained at a studio which courted celebrities, that of G.L. Manuel frères. Thus, she already had an address book of important clients. In order to keep them, she developed a trademark style that replicated the drama of Hollywood glamour shots. Her other inspiration was cinematographer Henri Alekan, the eye behind films such as Cocteau’s “Beauty and the Beast” or Wim Wenders’ “Wings of Desire”.

A year ago, Studio Harcourt turned seventy-five, an anniversary marked by the book Studio Harcourt 1934–2010. This volume describes the central trick of their portraiture as emphasising a subject’s eyes, nose and mouth.

The Harcourt portrait remains a talisman of success, not just for stars but also among bourgeois families. Although the studio survived both war and the Occupation, it almost foundered during the early 1990s. By overseeing the purchase of its archive for the nation, then-Culture Minister Jack Lang managed to save it.

Studio Harcourt also survived the transition to digital. In order to retain their signature retro graininess, its staff now uses 16 to 20 million pixels. Their cabine photo – which took a year to develop – uses no flash. It offers instead a mini-version of that lighting (eight or more projectors) that creates the famous ‘Harcourt halo’. Now, for ten euros, anyone can engineer a simulation of the €1,900 Harcourt sitting. The only requirement is a trip to the booth, inside the MK2 cinema next to the Mitterand library.

Like the enterprising photo blog the Paris mairie launched this summer, this cabine is about consolidating a heritage. In a city digitised non-stop by strangers, a new opinion of visual ownership is emerging. In an environment full of Flickr snaps and photo walls, it creates a place for the regard of real Parisians.

Throughout August, for instance, venerable photo agency Roger-Viollet worked with the mairie. With their help, the blog presented a different Parisian treasure every day. The same month saw an unveiling of personal souvenirs from the 1944 Liberation of Paris. These were found during a year-long appeal, which uncovered eight hundred items.

Or, to celebrate the tenth year of Paris Plage, one could see the free expo Paris sur Seine. (The name is a pun whose sound also means “Paris onstage”). A visual history of how Parisians have lived with their river, it offered the historic view of an ever-changing relationship.

These initiatives to honour the photo intend to make one think about its ownership. From the fabulous archives held by the state down to the public booth and family album, Paris maintains it offers the photograph a special home. The subtext of this claim is primacy. No matter how often the same snap is taken – or how far it travels – Paris demands that you think a little harder about its provenance.