Two odd birds for Tate Britain

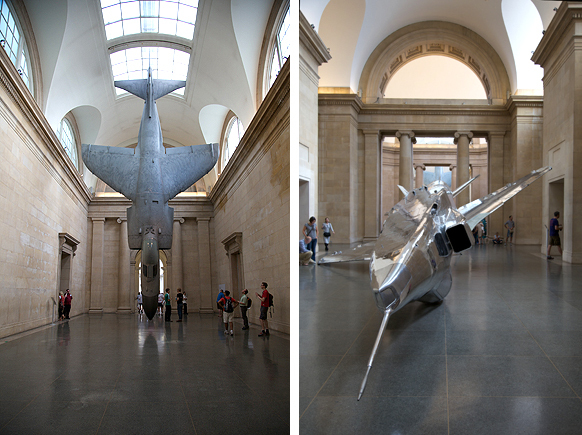

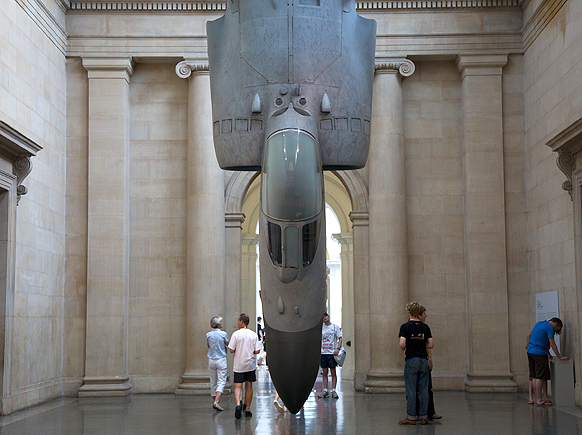

The objects, one hanging suspended and the other lying side-swiped, are decommissioned war aircraft. They comprise the Tate Britain Gallery’s 2010 Duveen Commission by artist Fiona Banner. The curator is Tate Britain’s Lizzie Carey-Thomas.

Ms. Banner admits to a long obsession with fighting aircraft. She once created as art a “wordscape” by transcribing the whole of the movie ‘Top Gun’. Her studio in East London also houses the wing of a RAF Tornado jet.

Her Sea Harrier ZE695 (named after the Harrier species of predatory hawk) first flew in the late 1980s. Its career ended in 2000 at Yeovilton when it crash-landed with a burst tire – forcing its pilot to eject and abandon it. In the Tate, it hangs upended from the ceiling like a trussed bird.

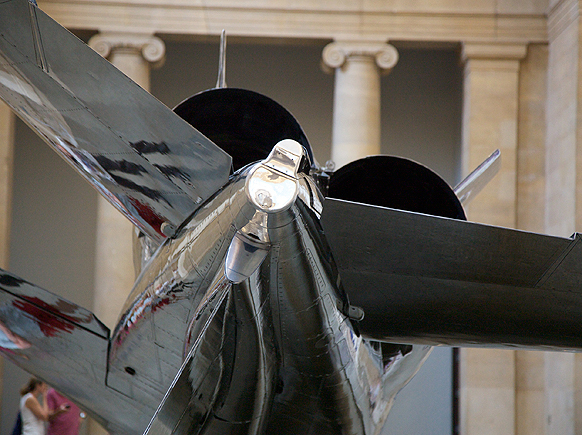

The Sepecat Jaguar, in contrast, has been stripped of its skin. It is as shiny as a piece of treasured heirloom silver. This polish is important, Ms. Banner maintains, “because you have to see yourself reflected in it; you are unable to detach yourself from the object.”

Lying on one wing, it seems fatally wounded. But because it measures sixteen metres and weighs in at seven tones, the Jaguar retains a definite sense of muscle. In an earlier life, it flew missions in Bosnia and saw action as a part of Desert Storm. It was retired from service in 2006.

The engineering feats required to position the two machines proved awesome. Each had to be broken down into small elements, before being slowly re-assembled, rivets and all.

Mock shock and awe was not the aim of the installation. Banner stresses she is not making “any kind of black and white statement”. Instead, she wants us to confront the objects’ beauty and seduction, “because the fact that we find them beautiful brings into question the very notion of beauty.” Why? Because fighter planes are designed for one function. They are calculated to seek out their prey, then kill it.

The sensation these ‘birds in space’ creates is unexpected. Both allude to a British romance with aeronautics, with World War I aces and World War II heroes. Their presentation also falls during the 70th anniversary of the London Blitz. Thus it evokes everything from Churchill’s praise of the Royal Air Force and its ‘Few’ to Monty Python’s later sketch (“I wish to join the Few, Sir!”…”I’m sorry, there are far too many.”)

The planes also look powerfully like captured game, birds treated like the grouse or pheasants still shot here for sport. Seeing them in these neo-Classical galleries also brings to mind the still life painting traditions of nature morte and trophées du chasse. Epitomised by 18th century painters such as Jan Weenix, examples of these grace both museums and country houses throughout Europe. Harrier, the hanging plane, has even been hand-painted with feathers by the artist.

Banner herself prefers to say little about her piece. Nevertheless, she likes to highlight one memory – to which she traces her fascination with planes. This occurred when she was a youngster, walking with her father in Wales. “We were in the hills, where it was quiet and very beautiful. Then, suddenly out of nowhere, this Harrier jump jet streaked by. It completely ripped up the sky; it utterly changed the moment.”