Swordsman, tranny, soldier, spy

Charles-Geneviève-Louis-Auguste-André-Timothée d’Eon de Beaumont (1728 – 1810) led a life that, two centuries later, still seems unbelievable. Author, master swordsman, diplomat and secret agent, he earned one of his century’s rarest distinctions: l’Ordre Royal et Militaire de Saint-Louis. His life in Russia, Paris and London was also distinguished by the fact that he spent 49 years of it as a man, then 33 as a woman. He also spent half of it in London, where the National Portrait Gallery just installed his portrait.

In this portrayal, the flamboyant nonconformist looks ordinary. His white lace fichu hides no décolletage – and his chubby face is stubbly. The portrait specialist from whom the Gallery bought it recognised the subject because, as he told the Guardian, it was clearly “a bloke in a dress”.

But what a bloke! The Chevalier is one Frenchman (and woman) who could teach the English about eccentricity. Slightly-built, he liked to swagger around in a dragoon’s uniform just as much as he loved sword-fighting in skirts. D’Eon, who called himself “Mademoiselle”, claimed that he was born coiffé or covered in foetal membranes. His true sex, he insisted, was a mystery from the start.

There was nothing ambiguous, however, about his talents. After his start as a Royal censor, d’Eon was snapped up by Louis XV for le Secret du Roi. This was a team of spies who answered directly to the King and worked behind the backs of government. At the start of the Seven Years’ War, Louis dispatched d’Eon to Russia to make an ally out of Empress Elisabeth. The Chevalier later claimed he gained her trust as a woman under the pseudonym of “Lia de Beaumont”.

Whatever the truth, d’Eon pulled off the daunting mission. Impressed, Louis raised him to a captaincy in the dragoons (which provided a uniform d’Eon paraded for years). The Chevalier was a brave soldier, wounded twice before the war’s end. When it finished, the King sent him to London to work on the peace treaty. In 1763, d’Eon saw this signed in Paris, received his Cross of Saint-Louis in thanks, then returned to London as the interim French ambassador. The posting was a bit of a ruse since, in his spy capacity, d’Eon was actually helping Louis plan to invade Britain.

It was just the the sort of contradictory status d’Eon relished. He went to town as “ambassador”, spending lavishly and schmoozing key British aristocrats. (His secret weapon: fine wines from his home in Burgundy). London society, however, was perplexed; diplomats rarely tried to keep their sex mysterious. D’Eon bemused Londoners so much that the stock exchange started taking bets about his sex. It didn’t help that the Chevalier had friendships among the libellistes. These were French expatriates who, from the safety of London, produced pornographic publications about the royals at home.

The Chevalier’s professional downfall was as spectacular as his rise. When a French count named de Guerchy arrived as the real ambassador, d’Eon refused to give up his post. Instead, he feuded publicly with his replacement and – perhaps influenced by his sleaze-peddling pals – scandalised the city with a tell-all book. Since it contained diplomatic secrets, this was a clear threat to reveal the King’s invasion plans. The result was fourteen years of political exile, with a shaken Louis afraid to let him back into France.

The blackmailed King did provide a generous pension. D’Eon used this windfall to indulge his bibliomania, amassing more than 6,000 rare books and manuscripts. Then, when Louis XV died in 1774, d’Eon demanded that the new King bring him back. This time, however, he added a condition: the French government had to recognise him as a woman. Pierre de Beaumarchais, author of “The Marriage of Figaro”, was put in charge of organising his homecoming. It took a twenty-page treaty and a grant for the Chevalier’s “wardrobe”. (The new King had ordered that d’Eon dress full-time as a woman).

King Louis and Marie Antoinette did receive d’Eon. But their Court had no place for the be-skirted Chevalier, who ended up back in Burgundy living with his mum. Four years before the start of the French Revolution, he threw in the towel and sailed for London – the capital he saw as “even more free than Holland”. When the Bastille was taken in 1789, his military enthusiasms were reawakened (d’Eon himself had once spent nineteen days in a château dungeon). However, no one took up his offer to lead a women’s brigade and his Royal pension was lost to the Revolution.

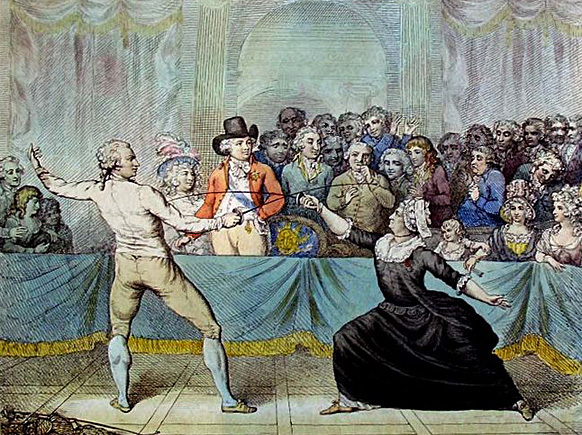

As a result, d’Eon drifted into penury. Forced to sell his rare books, staging duels for pay, the Chevalier spent his final years boarding with a naval widow by the name of Mrs. Cole.

He even spent a little time inside debtor’s prison. But the Chevalier d’Eon remained incorrigible, battling his poverty with sequential pleas to publishers. He assured each of them his memoirs would be rich in scandal but, before he could deliver, the Chevalier was felled by a stroke. Today he is remembered as namesake of the Beaumont Society – an English group who aim to smooth the way for cross-dressers and the trans-gendered. May they enjoy their lives as much as d’Eon did!

• Want to know more about d’Eon’s world? His pals the libellistes ranged from authors to defrocked priests. To meet them, try The Forbidden Bestsellers of Pre-Revolutionary France, by Harvard’s Robert Darnton or Blackmail, Scandal, and Revolution by Simon Burrows of Leeds University.

• Leed University Library also has a collection that belonged to d’Eon, including a copy of Catullus inscribed as a gift from John Wilkes to “Mademoiselle”.