London's first public gallery

Who gave Londoners their first picture gallery? A coalition of castaway children and high society, led by an arriviste, outspoken sea captain! Although it sounds completely improbable, this is a story you can still see for yourself. Just pay a visit to the Foundling Museum in Bloomsbury.

Londoners are acutely aware of fashion and this was no different in the 18th century. Then, as the booming city’s population doubled, the needs of the poor became increasingly visible. Private charities intending to help with their needs started to sprout all across the city. Each competed to attract influential sponsors.

The first to receive the royal charter (in 1739) was a “Hospital for the Maintenance and Education of Exposed and Deserted Children”. These ‘children’ were actually illegitimate babies, who were being literally left in the streets. The new institution’s list of Governors, however, made a stark contrast to its unfortunate objects of concern. In addition to half-a-dozen Earls and even more Dukes, it included artist William Hogarth and the composer Handel.

Soon known merely as the Foundling Hospital, the charity built some grand premises on fifty-six acres in north London. The organisation had been created by Thomas Coram, a seaman and ship-builder who had made his fortune in America. Coram had campaigned for years to rescue those Charles Dickens later labelled “the blank children”.

When he finally succeeded, Hogarth immortalised Coram’s benevolence with a portrait. Today the old sailor’s Hospital itself is memorialised – on its original site, by the Foundling Museum.

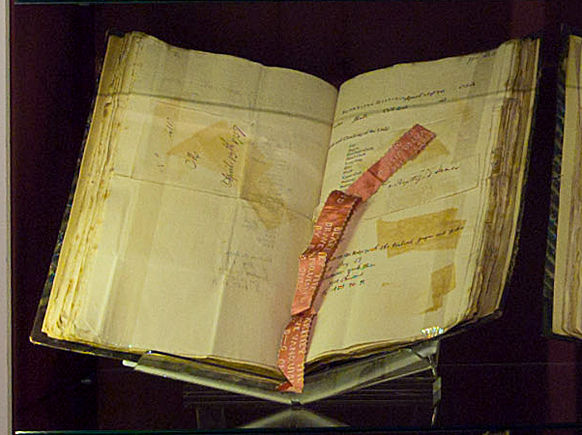

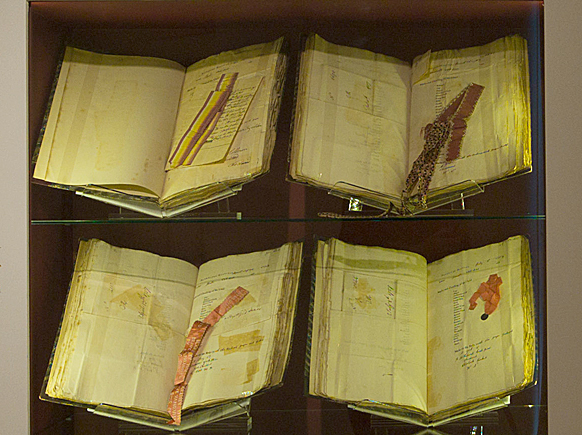

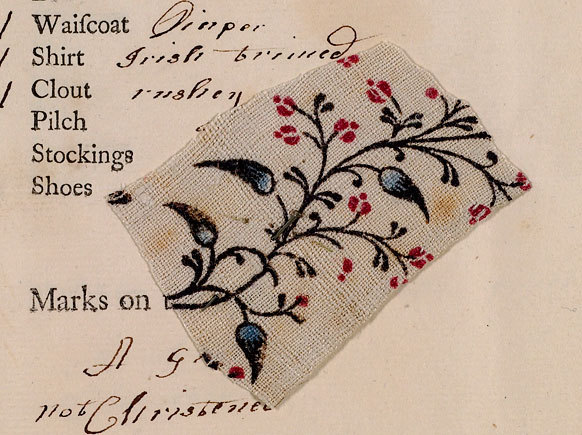

The Hospital required “all Persons who bring children to affix on each child some particular writing or distinguishing mark or token so that the children may be known hereafter.” All these markers were kept, in case a mother should reappear. Although the relics (rusty keys, pins, ribbons and beads, etc) make a sad display, the Hospital’s own story was one of great social success.

This was because Coram’s friends made his orphanage a magnet for high society. Painter William Hogarth, involved from the start, designed both the charity’s coat of arms and its children’s uniforms. The artist’s involvement was not entirely selfless, however, since he stood to gain some prize commissions. After all, the boardrooms of every London charity welcomed prosperous Governors who wanted their images hung on the walls.

The same marketing tactic applied to a very different hot spot: the era’s somewhat notorious Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens. Here, contemporary art was hung in the ‘supper boxes’. The more popular works, copied as engravings, usually became best-sellers.

So Hogarth was happy to help create a Hospital Picture Gallery: London’s first-ever spot where local artists could show new work. By 1760, Coram’s fund-raisers featured a yearly Picture Show with works by leading English artists. Visiting this was so à la mode the crowds became enormous, leading the painters concerned to seek a calmer venue. Eventually, their “Society of Artists of Great Britain” became the Royal Academy of Arts.

The Hospital’s other great promoter was George Friedriech Handel. A Royal favourite (and naturalised Briton), Handel created music for the King and Queen. Like Hogarth, he knew “good works” would impress his patrons. But Handel went the extra mile for Coram; his first concert in the Hospital’s unfinished chapel ended dramatically with the Hallelujah Chorus. It brought a huge ovation, led by the Prince and Princess of Wales.

Thanks to Hogarth and Handel, writes historian Liza Picard, “the done thing was to take the carriage out to the Hospital, see the touching young orphans, listen to some good music, enjoy the pictures…and get a glow of virtue donating to its funds.”

As for the actual orphans, between 1741 and 1799, the Foundling Hospital admitted over 18,000. Less than two hundred ever saw their mothers again, yet the institution’s policies saved – and changed – lives. The infants it accepted were innoculated against smallpox (an especially progressive measure for the time). Until the boys were apprenticed and the girls placed in service, all children got regular exercise, sensible food and training. They also received a basic education. (The Hospital continued to do its work until 1954, helping over 27,000 children).

At today’s Foundling Museum, one can enjoy the same pleasures as its early patrons. Both the Court Room and Picture Gallery have been reconstructed, to house the very treasures that attracted those Georgian trendies. The Hospital’s level of fame is illustrated by many rarities – such as a Chinese porcelain bowl from faraway Jiangxi. One of a set ordered in 1790, it juxtaposes a view of the Hospital with one of the Pleasure Gardens. Both are presented as equivalent social meccas.

If doubt still persists about the Hospital’s stature, one need only view its Handel Collection, which is stuffed with personal memorabilia. Concerts and recitals also still take place, just as they did three centuries ago.

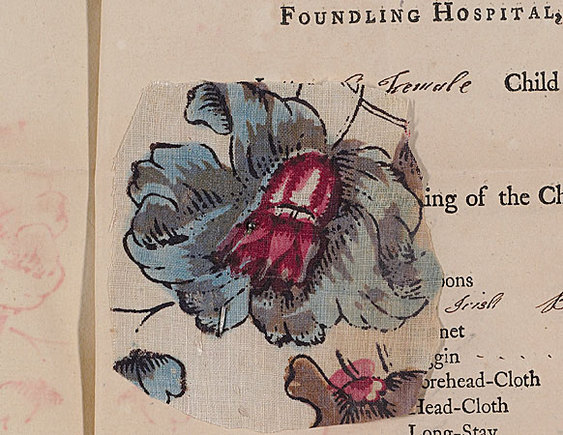

The Museum has made modern news, too, with its groundbreaking exhibition Threads of Feeling. This show, which examines the textile tokens left by desperate mothers, was curated by the expert John Styles. His work revealed that the Hospital owns Britain’s biggest collection of everyday 18th century textiles. Styles puts these evocative scraps into a poetic context, while pointing out how they help us understand the era.

Although the women who wore them were extremely poor, the fragments they relinquished are unique. In addition to their many “rich” motifs, Styles found silks from Lyon and Spitalfields, and a huge range of patterns printed on simple fabrics. The exhibit is a testament to the Industrial Revolution and the fact it brought bright images within every citizen’s reach.

These sad strips and swatches were deposited as tokens because of their visual interest. However, they demonstrate something that remains true today: even the most ‘reduced’ Londoners retain some relationship to what is fashionable.