Christian Lacroix in the Middle East

Today items such as the burqa have become political tools. Yet, at the Musée de Quai Branly, a former couturier and a curator have framed a look back into the world they first inhabited. The portrait that emerges from L’Orient des Femmes vu par Christian Lacroix is a special one. This is because the world it reveals is so firmly female.

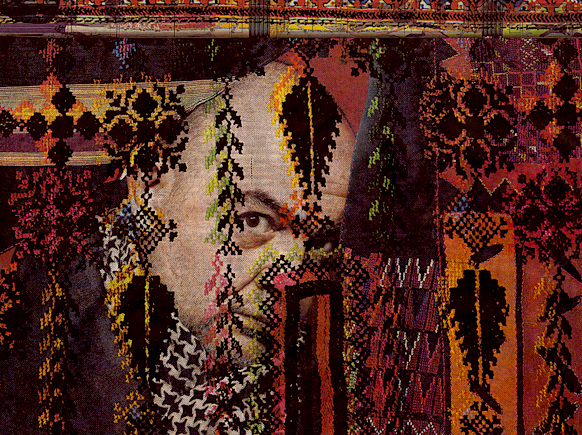

Conceived by the Lebanese-born expert Hada Al-Banna-Chidiac and lavishly staged by Lacroix, this exposition offers a singular journey. It introduces viewers to women of the “Fertile Crescent” (Egypt, Assyria, Mesopotamia, Palestine and Babylon) by showing what they wore from 1880 onwards.

Moving from northern Syria through the Sinai desert, the journey begins with a stunning medieval dress. Dating from the 13th century, it was discovered in 1991 – on the mummified body of a two year-old girl in Lebanon . Its tiny T-shaped silhouette spreads out into a triangle, thanks to cleverly inserted, bias-cut panels. Like all the garments in the exhibition, it remains richly embellished with silk embroidery. Lacroix hails its triangular template (echoed in all the robes on show) with a series of geometric neon icons.

Mme Chidiac chose Lacroix to keep her show from turning into “another ethnographic parade”. She wanted its magnificent robes shown in a context that suggested the lives of the women who created them. Thus the duo worked hard to combat stereotypes, by juxtaposing the clothes with contemporary observations and “exotic” film clips. From the start, says Lacroix, traders and explorers reported from the Middle East through a “dual filter” of their own perceptions: first, their views about Antiquity, then beliefs that came from their Bibles. “The veiled women of these villages seemed inaccessible and mysterious. This soon gave birth to both legends and fantasies.”

Why such females spurred foreign imaginations is clear. From region to region, tradition’s T-shape dominated their garments. Yet, the decoration, in joyously vibrant colours and patterns, remains explosive. Christian Lacroix, whose own couture is known for exuberance, says he is entranced by the lives behind the pieces. “The women’s mothers taught them the traditions and the embroideries. But every robe became the vehicle of its owner’s hopes. It was a symbol of audacity as well as tradition. These robes said, ‘I protect myself but also I make myself beautiful’. So their very humility became a demonstration of strength.”

Of special interest, he says, are the backs of all the garments. “Because, often, they seem stronger than the front. That provides an element of pride and also a provocation. These were women who knew others would see them from that angle.” In homage to them, Lacroix created display units in the form of dowry chests. These house traditional jewellery and wedding accessories: part of the future each woman imagined as she stitched.

Assembling the garments and their accessories took Mme Chidiac more than three years. In 2007, she received an unexpected bonus, from Jordanian costume expert Madame Widad Kamel Kawar. Mme Kawar agreed to loan articles from her own collection and the result has expanded the show’s authority. Even though many pieces here hail from nomadic tribes (or small villages), each one offers a truly sumptuous mosaic. The robes are strikingly suspended along a darkened ‘path’, which is sprinkled with allusions in the form of fully-dressed mannequins, blown-up period photos, wedding trousseaux and coffers of jewellery.

The designer, who closed his couture house in 2009, has a Sorbonne degree in museum studies. But, for “M. Lacroix”, this project is more about personal memories. In addition to the black-and-white newsreels of his childhood (and exotic illustrations in the Arabian Nights), a seafaring grandfather sent him numerous postcards from the Middle East. Often hand-coloured, these depictions of “local costumes” exuded a long-lasting fascination. “Later, when I encountered those women’s real-life relatives, I was deeply inspired by their sense of colour and elegance.” They helped him learn, he says, how marry form with colour, tradition with innovation.

One thing their ghostly presence here emanates is joy. These are magnificent, sparkling and radiant works; nothing about them is humourless or repressed. Even a Jordanian Bedouin captured on film early in the last century giggles as, in eighty seconds, she demonstrates the usefulness of three-and-a-half-metres of fabric. Such upbeat openness permeates the whole exposition.

Since leaving the couture, Lacroix has reinvented himself. Always adventurous enough to design uniforms (such as those for Air France and the TGV), he now keeps busy creating costumes for opera and theatre, helping to design hotels and working on his own line of furniture. However, he treats the Quai Branly pieces as couture. The show proceeds like a ghostly defilé and even finishes up with a robe de mariée.

Along the way, one discovers fabulous burquas – face veils – encrusted with shining beads, embroideries, seashells and actual coins. “The Bedouin women who made them,” says Lacroix, “carried their dowries on them”. Bedouin brides and married women did cover their faces but these parures du visage were not worn by girls. Each burqua indicated, by its colour, cut and style, the age and tribal affiliation of its wearer. Women made their own and each is highly personalised.

Is there a message here? “Yes,” says Mme Chidiac. Visitors are able to learn which patterns were created to foil the evil eye, why the women of Syria preferred to use the colour red, and how, early last century, Palestinian women’s talent made Bethlehem the ‘Paris of embroidery’. “But,” says Mme Chidiac, “Islam never imposed the veil upon its women. If there is one thing we should convey, that would be it.”